The <picture> element doesn't render anything on its own, but instead acts as a decision engine for an inner <img> element,

telling it what to render. <picture> follows a precedent already set by the <audio> and <video> elements: a wrapper element

that contains individual <source> elements.

<picture>

<source …>

<source …>

<img …>

</picture …>

That inner <img> also provides you with a reliable fallback pattern for older browsers without support for responsive images:

if the <picture> element isn't recognized by the user's browser, it's ignored. The <source> elements are then discarded as well,

since the browser either won't recognize them at all, or won't have meaningful context for them without a <video> or <audio> parent.

The inner <img> element will be recognized by any browser, though—and the source specified in its src will be rendered as expected.

"Art directed" images with <picture>

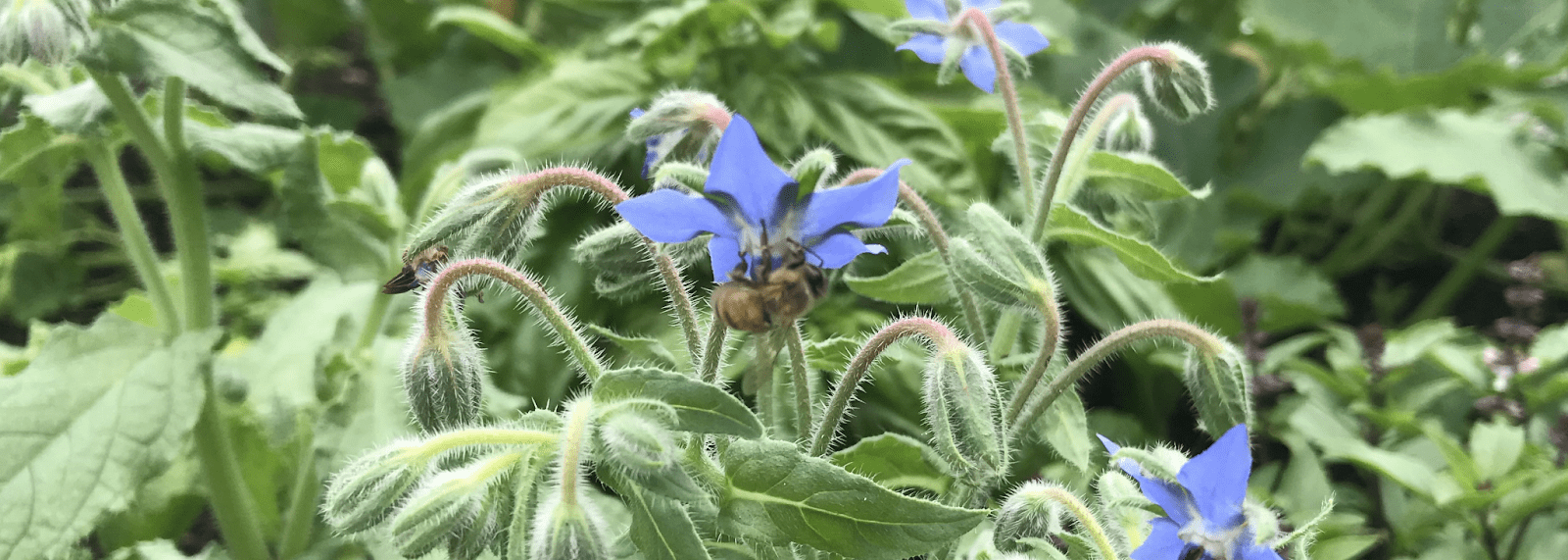

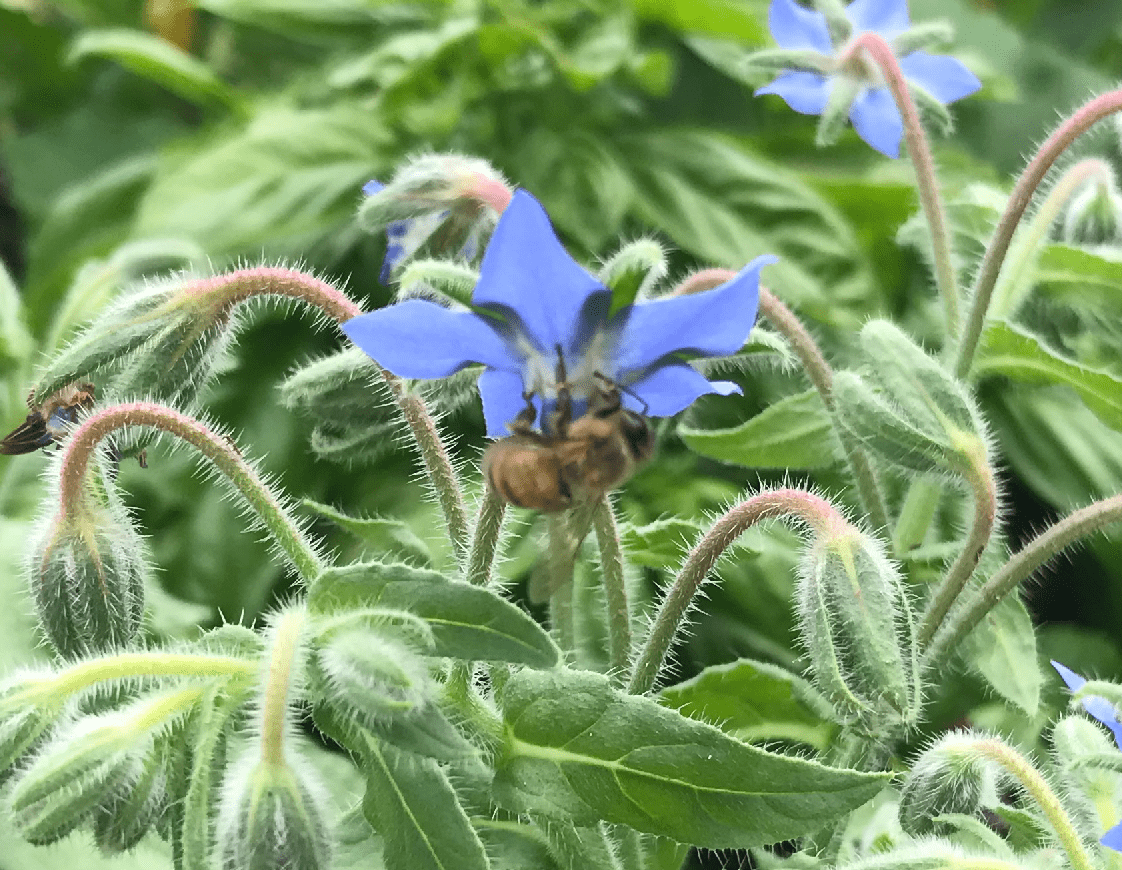

Making changes to the content or aspect ratio of an image based on the size of the image in the page is typically referred to as "art directed"

responsive images. srcset and sizes are designed to work invisibly, seamlessly swapping out sources as the user's browser dictates.

There are times, however, where you want to alter sources across breakpoints to better highlight the content, the same way you adapt page layouts.

For example: a full-width header image with a small central focus may work well on a large viewport:

But when scaled down to suit small viewports, the central focus of the image might be lost:

The subject of these image sources are the same, but in order to better focus on that subject visually, you'll want the proportions of the image source to change across breakpoints. For example, a tighter zoom on the center of the image, and some of the detail at the edges cropped out:

That sort of "cropping" can be achieved through CSS, but would leave a user requesting all the data that makes up that image, even though they might never end up seeing it.

Each source element has attributes defining the conditions for the selection of that source: media, which accepts a

media query, and type, which accepts a media type (previously known as "MIME type"). The first <source> in the source

order to match the user's current browsing context is selected, and the contents of the srcset attribute on that source

will be used to determine the right candidates for that context. In this example, the first source with a media attribute

that matches user's viewport size will be the one selected:

<picture>

<source media="(min-width: 1200px)" srcset="wide-crop.jpg">

<img src="close-crop.jpg" alt="…">

</picture>

You should always specify the inner img last in the order—if none of the source elements match their media or type

criteria, the image will act as a "default" source. If you're using min-width media queries, you want to have the largest

sources first, as seen in the preceding code. When using max-width media queries, you should put the smallest source first.

<picture>

<source media="(max-width: 400px)" srcset="mid-bp.jpg">

<source media="(max-width: 800px)" srcset="high-bp.jpg">

<img src="highest-bp.jpg" alt="…">

</picture>

When a source is chosen based on the criteria you've specified, the srcset attribute on source is passed along to the

<img> as though it were defined on <img> itself—meaning you're free to use sizes to optimize art directed image

sources as well.

<picture>

<source media="(min-width: 800px)" srcset="high-bp-1600.jpg 1600w, high-bp-1000.jpg 1000w">

<source srcset="lower-bp-1200.jpg 1200w, lower-bp-800.jpg 800w">

<img src="fallback.jpg" alt="…" sizes="calc(100vw - 2em)">

</picture>

Of course, an image with proportions that can vary depending on the selected <source> element raises a performance issue:

<img> only supports a single width and height attribute, but omitting those attributes can lead to a measurably worse user experience.

In order to account for this, a relatively recent—but

well supported—addition to the HTML

specification allows for use of height and width attributes on <source> elements. These work to reduce layout shifts just as well

as they do on <img>, with the appropriate space reserved in your layout for whatever <source> element is selected.

<picture>

<source

media="(min-width: 800px)"

srcset="high-bp-1600.jpg 1600w, high-bp-1000.jpg 1000w"

width="1600"

height="800">

<img src="fallback.jpg"

srcset="lower-bp-1200.jpg 1200w, lower-bp-800.jpg 800w"

sizes="calc(100vw - 2em)"

width="1200"

height="750"

alt="…">

</picture>

It's important to note that art direction can be used for more than decisions based on viewport-size—and it should, given that

the majority of those cases can be more efficiently handled with srcset/sizes. For example, selecting an image source better

suited to the color scheme dictated by a user's preference:

<picture>

<source media="(prefers-color-scheme: dark)" srcset="hero-dark.jpg">

<img srcset="hero-light.jpg">

</picture>

The type attribute

The type attribute allows you to use the <picture> element's single-request decision engine to only serve image formats

to browsers that support them.

As you learned in Image Formats and Compression, an encoding that the browser can't parse won't even be recognizable as image data.

Before the introduction of the <picture> element, the most viable front-end solutions for serving new image formats required

the browser to request and attempt to parse an image file before determining whether to throw it away and load a fallback. A

common example was a script along these lines:

<img src="image.webp"

data-fallback="image.jpg"

onerror="this.src=this.getAttribute('data-fallback'); this.onerror=null;"

alt="...">

With this pattern, a request for image.webp would still be made in every browser—meaning a wasted transfer for browsers

without support for WebP. Browsers that couldn't then parse the WebP encoding would throw an onerror event, and swap

the data-fallback value into src. It was a wasteful solution, but again, approaches like this one were the only option

available on the front-end. Remember that the browser begins making requests for images before any custom scripting has a

chance to run—or even be parsed—so we couldn't preempt this process.

The <picture> element is explicitly designed to avoid those redundant requests. While there's still no way for a browser

to recognize a format it doesn't support without requesting it, the type attribute warns the browser about the source

encodings up-front, so it can decide whether or not to make a request.

In the type attribute, you provide the Media Type (formerly MIME type)

of the image source specified in the srcset attribute of each <source>. This provides the browser with all the information it

needs to immediately determine whether the image candidate provided by that source can be decoded without making any external

requests—if the media type isn't recognized, the <source> and all its candidates are disregarded, and the browser moves on.

<picture>

<source type="image/webp" srcset="pic.webp">

<img src="pic.jpg" alt="...">

</picture>

Here, any browser that supports WebP encoding will recognize the image/webp Media Type specified in the type attribute

of the <source> element, select that <source>, and—since we've only provided a single candidate in srcset—instruct the inner

<img> to request, transfer, and render pic.webp. Any browser without support for WebP will disregard the source, and

absent any instructions to the contrary, the <img> will render the contents of src as it has done since 1992.

You don't need to specify a second <source> element with type="image/jpeg" here, of course—you can assume universal support for JPEG.

Regardless of the user's browsing context, all of this is achieved with a single file transfer, and no bandwidth wasted on

image sources that can't be rendered. This is forward-thinking, as well: as newer and more efficient file formats will come

with Media Types of their own, and we'll be able to take advantage of them thanks to picture—with no JavaScript, no serverside

dependencies, and all the speed of <img>.

The future of responsive images

All of the markup patterns discussed here were a heavy lift in terms of standardization: changing the functionality of

something as established and central to the web as <img> was no small feat, and the suite of problems those changes aimed to

solve were extensive to say the least. If you've caught yourself thinking that there's a lot of room for improvement with these

markup patterns, you're absolutely right. From the outset, these standards were intended to provide a baseline for future

technologies to build on.

All of these solutions have necessarily depended on markup, so as to be included in the initial payload from the server,

and arrive in time for the browser to request image sources—a limitation that led to the admittedly unwieldy sizes attribute.

However, since these features were introduced to the web platform, a native method of deferring image requests was introduced.

<img> elements with the loading="lazy" attribute aren't requested until the layout of the page is known, in order to defer

requests for images outside of the user's initial viewport until later on in the process of rendering the page, potentially avoiding

unnecessary requests. Because the browser fully understands the page layout at the time these requests are made, a

sizes="auto" attribute has been proposed as an addition to the HTML specification

to avoid the chore of manually-written sizes attributes in these cases.

There are also additions to the <picture> element on the horizon as well, to match some exceptionally exciting changes

to the way we style out page layouts. While viewport information is a sound basis for high-level layout decisions, it

prevents us from taking a fully component-level approach to development—meaning, a component that can be dropped into

any part of a page layout, with styles that respond to the space that the component itself occupies. This concern led

to the creation of container queries: a method of styling elements

based on the size of their parent container, rather than the viewport alone.

While the container query syntax has only just stabilized—and browser support is very limited,

at the time of writing—the addition of the browser technologies that enable it will provide the <picture> element with a

means of doing the same thing: a potential container attribute that allows for <source> selection criteria based on the

space the <picture> element's <img> occupies, rather than based on the size of the viewport.

If that sounds a little vague, well, there's a good reason: these web standards discussions are ongoing, but far from settled—you can't use them just yet.

While responsive image markup promises to only get easier to work with over time, like any web technology, there are a number of services, technologies, and frameworks to help ease the burden of hand-writing this markup available. In the next module, we'll look at how to integrate everything we've learned about image formats, compression, and responsive images into a modern development workflow.