Allowing your pages to respond to different screen sizes is just one way of making sure your website is accessible to as many people as possible. Consider some of these other factors that you should keep in mind.

Color vision deficiency

Different people perceive color differently. People with protanopia don't perceive red as a distinct color. With deuteranopia, green is missing. For people with tritanopia, it's blue.

Some tools can give you a general idea of how your color schemes appear to people with different kinds of color vision.

Firefox's Accessibility tab includes a dropdown labeled Simulate with a list of options.

In Chrome DevTools, the rendering tab allows you to emulate vision deficiencies.

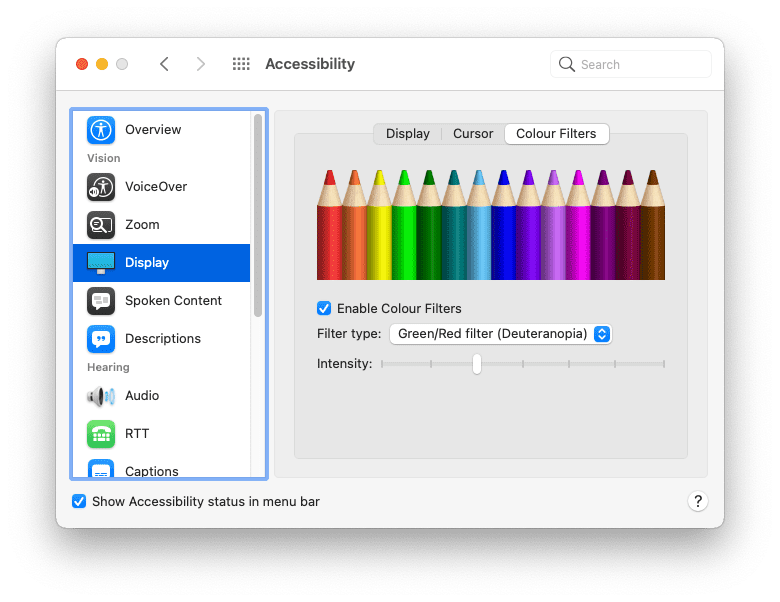

Those are browser-specific tools. It's also possible to emulate different vision types at the operating system level.

On the Mac, go to:

- System Preferences

- Accessibility

- Display

- Color Filters

- Enable Color Filters

Select one of the options.

In general it's not a good idea to rely purely on color to differentiate between different elements. For example, you can—and should—make your links a different color to the surrounding text. But you should also apply some other styling indicator like underlining the links or making them bold.

a { color: red; }

a { color: red; font-weight: bold; }

Color contrast

Some color combinations can cause trouble. If there isn't enough contrast between the foreground color and background color, text becomes difficult to read. Poor color contrast is one of the most common accessibility issues on the web, but fortunately, it's one that you can catch early in the design process.

Here are some tools you can use to test the contrast ratio of your text and background colors:

- VisBug is a browser extension available for all major desktop browsers.

- Firefox's Accessibility Inspector can check for issues with visual contrast.

- You can also discover and fix low-contrast text with Chrome DevTools.

- In Microsoft's Edge browser, you can test text-color contrast using the color picker.

It's a good idea to always declare color and background-color together in your CSS. Don't assume that the background color will be the browser default. People can and do change the colors used by their browser.

body { color: black; }

body { color: black; background-color: white; }

High contrast

Some people set their operating systems to use a high-contrast mode. You can try this on your operating system.

On the Mac, go to:

- System Preferences

- Accessibility

- Display

Select the option to increase contrast.

There's a media feature to detect if someone has enabled high contrast mode. The prefers-contrast media feature can be queried for three values: no-preference, less, and more. You can use this information to adjust your site's color palette.

People can also set a preference in their operating system to use inverted colors.

On the Mac, go to:

- System Preferences

- Accessibility

- Display

Select the option to invert colors.

Make sure your website still makes sense for someone browsing with inverted colors. Watch out for box shadows—these may need adjusting when colors are inverted.

Font size

Color isn't the only thing that people can adjust in their browser, they can also adjust the default font size. As their vision declines, they might adjust the default font size in their browsers or operating systems, bumping up the numbers with the passing of the years.

You can respond to these settings by using relative font sizes. Avoid using units like px. Use relative units like rem or ch instead.

Try changing the default text size setting in your browser. You can do that in your browser preferences. Or you can do it while you're visiting a web page by zooming in. Does your website still work if the default font size is increased by 200%? How about 400%?

Someone visiting your website on a desktop computer with their font size bumped up to 400% should get the same layout as someone visiting your site on a small-screen device.

Keyboard navigation

Not everyone uses a mouse or a trackpad to navigate web pages. A keyboard is another way of getting around a page, with the tab key being particularly useful. Users can quickly move from one link or form field to the next.

Links styled with the :hover and :focus pseudo-classes, will display those styles regardless of whether someone is using a mouse, a trackpad, or a keyboard. Use the :focus-visible pseudo-class to style your links for just keyboard navigation. You can make those styles extra noticeable.

a:focus,

a:hover {

outline: 1px dotted;

}

a:focus-visible {

outline: 3px solid;

}

As the user tabs from link to link or form field to form field, those elements will be focused in the order they appear in the document structure. This should also match the visual order.

Be careful with the CSS order property. You can use this in combination with flexbox and grid to place elements in a different visual order to their order in the HTML. That's a powerful feature but it could confuse people navigating with a keyboard.

Test your web pages by using the tab key on your keyboard to make sure that the tabbing order makes sense.

In the Accessibility panel of the Firefox browser's developer tools there's an option to Show Tabbing Order. Enabling this will overlay numbers on each focusable element.

Reduced motion

Animation and motion are wonderful ways to bring web designs to life. But for some people these movements can be very disorienting and even cause nausea.

There's a feature query that communicates whether the user would prefer less motion. It's called prefers-reduced-motion. Include it wherever you are using CSS transitions or animations.

a:hover {

transform: scale(150%);

}

@media (prefers-reduced-motion: no-preference) {

a {

transition-duration: 0.4s;

transition-property: transform;

}

}

The prefers-reduced-motion media query is specifically for movement on the screen. If you are using transitions on an element's color that shouldn't be affected by prefers-reduced-motion. It's also ok to transition opacity and cross-fade. Reduced motion doesn't have to mean no animation.

Voice

People experience the web differently. Not everyone is seeing your website on a screen. Assistive technologies such as screen readers convert the information output to a screen into spoken words.

Screen readers work with all kinds of applications including web browsers. In order for a web browser to communicate usefully with a screen reader, there needs to be useful semantic information in the web page currently being accessed.

Previously, you learned how icon-only buttons need to include an attribute to specify the button's purpose to non-sighted users. This is just one example of the importance of strong foundational HTML.

Headings

Use headings like <h1>, <h2>, <h3>, etc. sensibly. Screen readers use these headings to generate an outline of your document which can be navigated with keyboard shortcuts.

<div class="heading-main">Welcome to my page</div> <div class="heading-secondary">About me</div> <div class="heading-tertiary">My childhood</div> <div class="heading-secondary">About this website</div> <div class="heading-tertiary">How this site was built</div>

<h1>Welcome to my page</h1>

<h2>About me</h2>

<h3>My childhood</h3>

<h2>About this website</h2>

<h3>How this site was built</h3>Structure

Use landmark elements like <main>, <nav>, <aside>, <header>, and <footer> to structure your page's contents. Screen-reader users can then jump straight to these landmarks.

<div class="header">...</div> <div class="navigation">...</div> <div class="maincontent">...</div> <div class="sidebar">...</div> <div class="footer">...</div>

<header>...</header> <nav>...</nav> <main>...</main> <aside>...</aside> <footer>...</footer>

Forms

Make sure that every form field has an associated <label> element. You can associate a label with a form field using the for attribute on the <label> element and the corresponding id attribute on the form field.

<span class="formlabel">Your name</span> <input type="text">

<label for="name">Your name</label> <input id="name" type="text">

Images

Always provide a text description of images using the alt attribute.

<img src="dog.jpg">

<img src="dog.jpg" alt="A golden retriever sitting on the grass looking happy.">

If the image is purely presentational, you should still include the alt attribute but you can give it an empty value.

<img src="texture.png">

<img src="texture.png" alt="">

Jake Archibald published an article on writing great alt text.

Links

Try to provide descriptive text within links. Avoid using phrases like "click here" or "more."

<p>To find out more about our latest offers, <a href="/offers.html">click here</a>.</p>

<p>Find out more about <a href="/offers.html"> our latest offers</a>.</p>

ARIA

Using sensible semantic HTML will make your web pages more accessible to assistive technologies like screen readers and also to other audio outputs like voice assistants.

Some interface widgets that don't have a corresponding HTML element: carousels, tabs, accordions, and so on. Those need to be built from scratch with a combination of HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and ARIA.

ARIA stands for Accessible Rich Internet Applications. Its vocabulary allows you to provide semantic information when there isn't a suitable HTML element available.

If you need to create interface elements that aren't yet available as HTML elements, familiarize yourself with ARIA.

The more bespoke functionality you add with JavaScript, the more you'll need to understand ARIA. If you stick with native HTML elements, you may not need any ARIA.

If it's at all possible, test with real users of screen readers. Not only will this give you a better understanding of how they navigate the web, it will also take the guesswork out of designing with accessibility in mind.

Testing with actual people is a great way of exposing any assumptions you might be making. In the next module, you'll learn about the different ways people interact with your websites—another area where it's all too easy to make assumptions.

Check your understanding

Test your knowledge of accessibility

With CSS, a developer can overwrite a user preference like font size, for the worst?

body { font-size: 12px; } is enough.To avoid overwriting a user's font size preference, use?

px.rem.Everyone in the world uses a mouse.

An image with an empty alt attribute does what?