Introduction

You want your web app to feel responsive and smooth when doing animations, transitions, and other small UI effects. Making sure these effects are jank-free can mean the difference between a "native" feel or a clunky, unpolished one.

This is the first in a series of articles covering rendering performance optimization in the browser. To kick things off, we'll cover why smooth animation is difficult and what needs to happen to achieve it, as well as a few easy best practices. Many of these ideas were originally presented in "Jank Busters," a talk Nat Duca and I gave at Google I/O talk (video) this year.

Introducing V-sync

PC gamers might be familiar with this term, but it's uncommon on the web: what is v-sync?

Consider your phone's display: it refreshes on a regular interval, usually (but not always!) about 60 times a second. V-sync (or vertical synchronization) refers to the practice of generating new frames only between screen refreshes. You might think of this like a race condition between the process that writes data into the screen buffer and the operating system reading that data to put it on the display. We want the buffered frame contents to change in between these refreshes, not during them; otherwise the monitor will display half of one frame and half of another, leading to "tearing".

To get a smooth animation you need a new frame to be ready every time a screen refresh happens. This has two big implications: frame timing (that is, when the frame needs to be ready by) and frame budget (that is, how long the browser has to produce a frame). You only have the time between screen refreshes to complete a frame (~16ms on a 60Hz screen), and you want to start producing the next frame as soon as the last one was put up on the screen.

Timing is Everything: requestAnimationFrame

Many web developers use setInterval or setTimeout every 16 milliseconds to create animations. This is a problem for a variety of reasons (and we'll discuss more in a minute), but of particular concern are:

- Timer resolution from JavaScript is only on the order of several milliseconds

- Different devices have different refresh rates

Recall the frame timing problem mentioned above: you need a completed animation frame, finished with any JavaScript, DOM manipulation, layout, painting, etc, to be ready before the next screen refresh occurs. Low timer resolution can make it difficult to get animation frames completed before the next screen refresh, but variation in screen refresh rates makes it impossible with a fixed timer. No matter what the timer interval is you'll slowly drift out of the timing window for a frame and end up dropping one. This would happen even if the timer fired with millisecond accuracy, which it won't (as developers have discovered) -- timer resolution varies depending on whether the machine is on battery vs. plugged in, can be affected by background tabs hogging resources, etc. Even if this is rare (say, every 16 frames because you were off by a millisecond) you'll notice: you'll be dropping several frames a second. You'll also be doing the work to generate frames that never get displayed, which wastes power and CPU time you could be spending doing other things in your application.

Different displays have different refresh rates: 60Hz is common, but some phones are 59Hz, some laptops drop to 50Hz in low-power mode, some desktop monitors are 70Hz.

We tend to focus on frames per second (FPS) when discussing rendering performance, but variance can be an even bigger problem. Our eyes notice the tiny, irregular hitches in animation that a poorly timed animation can produce.

The way to get correctly timed animation frames is with requestAnimationFrame. When you use this API, you're asking the browser for an animation frame. Your callback gets called when the browser is soon going to produce a new frame. This happens no matter what the refresh rate is.

requestAnimationFrame has other nice properties too:

- Animations in background tabs get paused, conserving system resources and battery life.

- If the system can't handle rendering at the screen's refresh rate, it can throttle animations and produce the callback less frequently (say, 30 times a second on a 60Hz screen). While this drops framerate in half, it keeps the animation consistent -- and as stated above, our eyes are much more attuned to variance than framerate. A steady 30Hz looks better than 60Hz that misses a few frames a second.

requestAnimationFrame has been discussed all over the place already, so refer to articles like this one from creative JS for more info on it, but it's an important first step to smooth animation.

Frame Budget

Since we want a new frame ready on every screen refresh, there's only the time in between refreshes to do all the work to create a new frame. On a 60Hz display, that means we've got about 16ms to run all JavaScript, perform layout, paint, and whatever else the browser has to do to get the frame out. This means if the JavaScript inside your requestAnimationFrame callback takes longer than 16ms to run, you don't have any hope of producing a frame in time for v-sync!

16ms isn't a lot of time. Luckily Chrome's Developer Tools can help you track down if you're blowing your frame budget during the requestAnimationFrame callback.

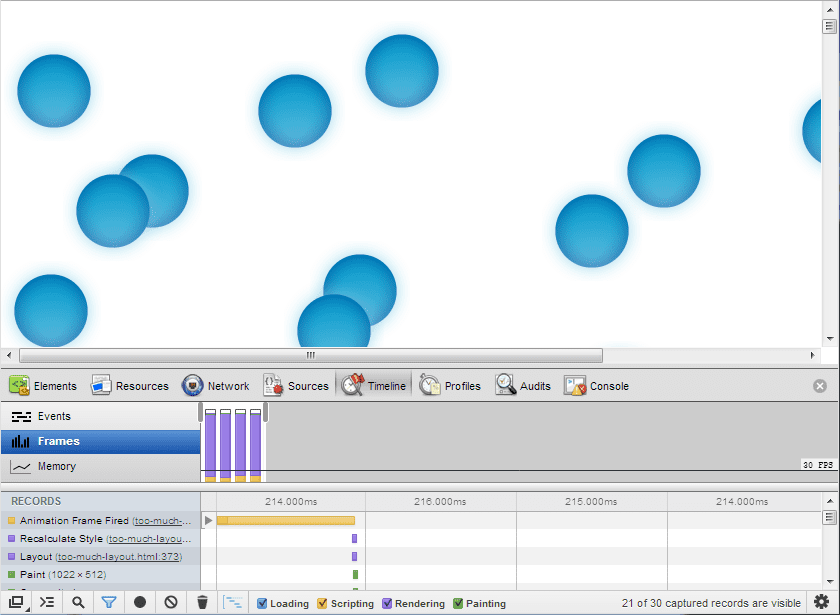

Opening up the Dev Tools timeline and taking a recording of this animation in action quickly shows that we're way over budget when animating. In Timeline switch to "Frames" and take a look:

Those requestAnimationFrame (rAF) callbacks are taking >200ms. That's an order of magnitude too long to tick out a frame every 16ms! Opening up one of those long rAF callbacks reveals what's going on inside: in this case, lots of layout.

Paul's video goes into more detail about the specific cause of the relayout (it's reading scrollTop) and how to avoid it. But the point here is that you can dive into the callback and investigate what's taking so long.

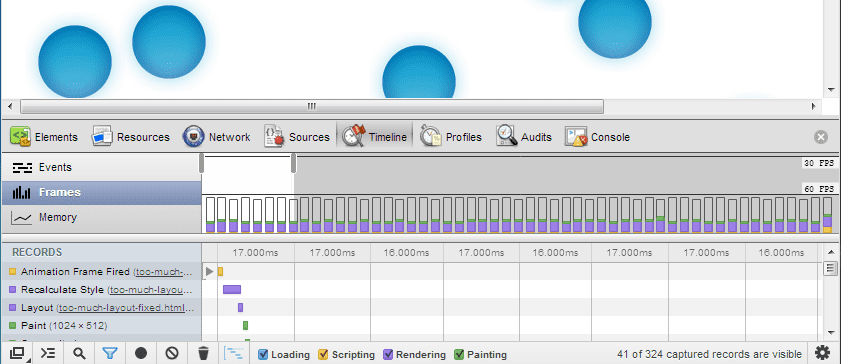

Notice the 16ms frame times. That blank space in the frames is the headroom you have to do more work (or let the browser do work it needs to do in the background). That blank space is a Good Thing.

Other Source of Jank

The biggest cause of trouble when trying to run JavaScript-powered animations is that other stuff can get in the way of your rAF callback, and even prevent it from running at all. Even if your rAF callback is lean and runs in just a few milliseconds, other activities (like processing an XHR that just came in, running input event handlers, or running scheduled updates on a timer) can suddenly come in and run for any period of time without yielding. On mobile devices sometimes processing these events can take hundreds of milliseconds, during which time your animation will be completely stalled. We call those animation hitches jank.

There's no magic bullet to avoid these situations, but there are a few architectural best practices to set yourself up for success:

- Don't do a lot of processing in input handlers! Doing a lot of JS or trying to rearrange the whole page during e.g. an onscroll handler is a very common cause of terrible jankiness.

- Push as much processing (read: anything that'll take a long time to run) into your rAF callback or Web Workers as possible.

- If you push work into the rAF callback, try to chunk it up so you're only processing a little bit each frame or delay it until after an important animation is over -- this way you can continue to run short rAF callbacks and animate smoothly.

For a great tutorial covering how to push processing into requestAnimationFrame callbacks rather than input handlers, see Paul Lewis's article Leaner, Meaner, Faster Animations with requestAnimationFrame.

CSS Animation

What's better than lightweight JS in your event and rAF callbacks? No JS.

Earlier we said there's no silver bullet for avoiding interrupting your rAF callbacks, but you can use CSS animation to avoid the need for them entirely. On Chrome for Android in particular (and other browsers are working on similar features), CSS animations have the very desirable property that the browser can often run them even if JavaScript is running.

There's an implicit statement in the above section on jank: browsers can only do one thing at a time. This isn't strictly true, but it's a good working assumption to have: at any given time the browser can be running JS, performing layout, or painting, but only one at a time. This can be verified in the Timeline view of Dev Tools. One of the exceptions to this rule is CSS animations on Chrome for Android (and soon desktop Chrome, though not yet).

When possible, using a CSS animation both simplifies your application and lets animations run smoothly, even while JavaScript runs.

// see http://paulirish.com/2011/requestanimationframe-for-smart-animating/ for info on rAF polyfills

rAF = window.requestAnimationFrame;

var degrees = 0;

function update(timestamp) {

document.querySelector('#foo').style.webkitTransform = "rotate(" + degrees + "deg)";

console.log('updated to degrees ' + degrees);

degrees = degrees + 1;

rAF(update);

}

rAF(update);

If you click the button JavaScript runs for 180ms, causing jank. But if instead we drive that animation with CSS animations the jank no longer occurs.

(Remember at the time of this writing, CSS animation is only jank-free on Chrome for Android, not desktop Chrome.)

/* tools like Modernizr (http://modernizr.com/) can help with CSS polyfills */

#foo {

+animation-duration: 3s;

+animation-timing-function: linear;

+animation-animation-iteration-count: infinite;

+animation-animation-name: rotate;

}

@+keyframes: rotate; {

from {

+transform: rotate(0deg);

}

to {

+transform: rotate(360deg);

}

}

For more information on using CSS Animations, see articles like this one on MDN.

Wrapup

The short of it is:

- When animating, producing frames for every screen refresh matters. Vsync'd animation makes a huge positive impact on the way an app feels.

- The best way to get vsync'd animation in Chrome and other modern browsers is to use CSS animation. When you need more flexibility than CSS animation provides, the best technique is requestAnimationFrame-based animation.

- To keep rAF animations healthy and happy, make sure other event handlers aren't getting in the way of your rAF callback running, and keep rAF callbacks short (<15ms).

Lastly, vsync'd animation doesn't only apply to simple UI animations -- it applies to Canvas2D animation, WebGL animation, and even scrolling on static pages. In the next article in this series we'll dig into scrolling performance with these concepts in mind.

Happy animating!